Family history research often brings to light little mysteries and I came across one recently. In mid Victorian times emigration to (amongst other places) Australia and New Zealand was in full swing. Both countries offered a better future than the immigrants could reasonably expect at home and advertisements like the one reconstructed above offered cheap, or even free, passages to their shores. There was obviously risk involved because a totally new life had to be created ‘down under’, but a greater risk had to be taken just to get there. In the days of sailing ships the number of shipwrecks was, to a modern eye, enormous. Hard to believe, but nevertheless true, between 1875 and 1883 the officially estimated losses of British merchant ships were 10,318, along with 21,224 seamen and 3,392 passengers. Bad weather, badly maintained ships, collisions at sea and sometimes incompetent or intoxicated crews all contributed to these extraordinary figures.

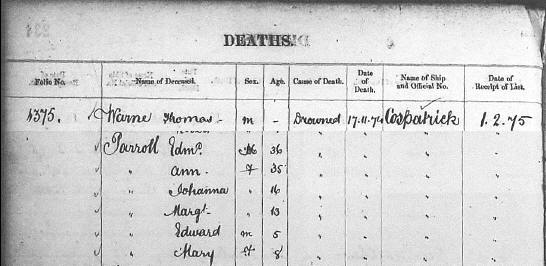

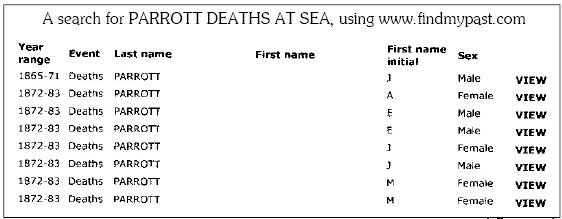

Looking for a topic for an article for this magazine I found transcripts of the GRO records of deaths at sea for the period 1865 to 1883 on the website www.findmypast.com and from this source found the names of eight P*RR*TTs lost at sea:

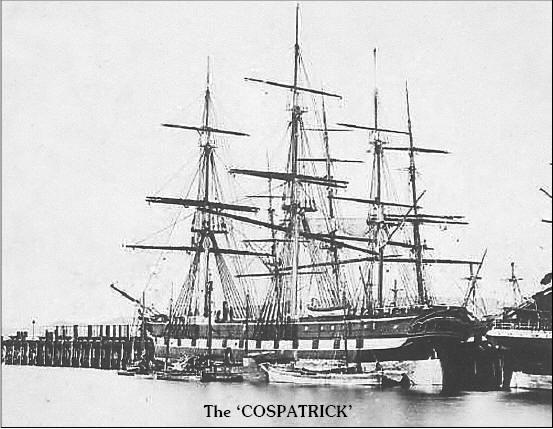

Trying to get more details of the people and their fate I looked at the pages of the register and found to my surprise that no fewer than 6 of them were from the same family and had perished when, in 1874, the sailing ship ‘COSPATRICK’ was lost in the South Atlantic . She was an elderly immigrant ship, built in Burma in 1856. This voyage started at Gravesend on 8 September 1874 and she sank on 18 November. Further investigation revealed that she had caught fire and although the cause of the fire was to be disputed the official verdict was that since spontaneous combustion was unlikely the source of ignition must have been a lucifer match or candle dropped during an attempt to broach (steal) the cargo by either the crew or emigrants. This convenient explanation avoided deeper investigation into the operating company’s methods or provision of safety equipment.

The results were devastating: out of about 433 passengers and a crew of about 46 only 6 survived to reach land and 3 of these expired shortly afterwards. As with the ‘Titanic’ nearly 40 years later there were insufficient lifeboats since the number required by law was based on the ship’s tonnage and no account was taken of the actual number of people on board. The whole episode was horrendous – the idea of ‘Women and Children First’ proved to be (not for the first time) nothing more than a pious saying. ‘Survival of the Fittest’ might have summed up the situation better. Women in the water were hampered by the voluminous clothes of the period which when waterlogged only served to drag the poor unfortunate woman down.

Launching of the ship’s lifeboats was difficult because of their position and lack of maintenance of the boats and their launching tackle. Of the 6 boats carried, 2 were burnt out, another capsized on being launched; another when launched, empty, floated away because it had not been made fast to the ship at the time of launching.

The 2 remaining boats got away, one with 32 souls on board, the other with 30. Subsequently they became separated and the first was never seen again. The second with only 6 left alive were rescued by the British Sceptre but 3 of these died shortly afterwards leaving just 3 (all seamen – no emigrants survived) to tell their story to the world. Lack of water and food had resulted in people in the boats drinking seawater and resorting to cannibalism.

There is no record of any of the ‘PARROTTs’ getting into either lifeboat and along with so many others they all slipped below the waves, never to know the new life in New Zealand which they had planned.